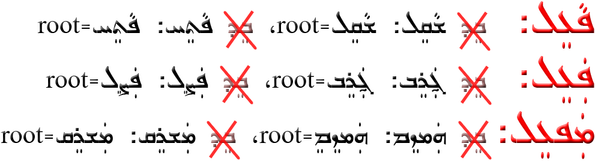

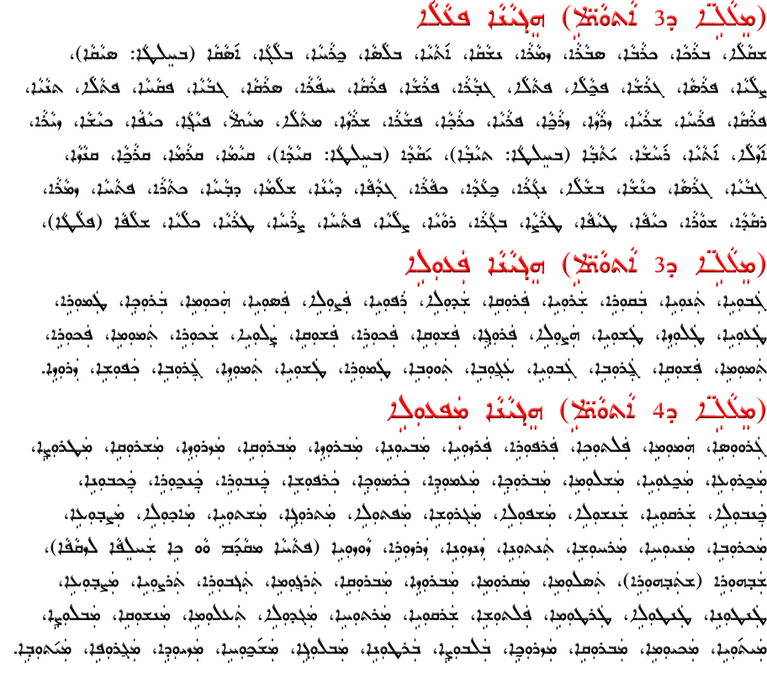

This page: 3 Weight of Verbs

In Assyrian, most of the words are derived from "verb". And those who do, follow the spelling and the originality of the verb they are derived from. Since the largest portion of our language is constructed on 'verb', in these series, the most emphasis will be put on 'verb, milta, ܡܸܠܬܵܐ.'

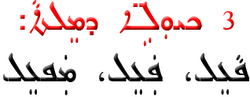

Three weights of Verb

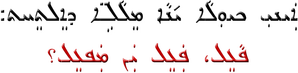

Apart of the verb indicating the time of an action (tenses)—past tense, happening now—present tense, or to be happened—future tense, in our language, the verb is divided into three different "weights". These three weights are put in formulas or patterns to be learned and discussed easily; much as the "Abgad, Haw'waz, Khat'tay…"

Of course, these three word-likes do not have a literal meaning, but they are merely "patterns" that represent the three different categories of verbs we have in Assyrian.

Simply put, each one of these patterns represents the verbs that 'weigh' like it,

Simply put, each one of these patterns represents the verbs that 'weigh' like it,

The Root of the verb

The simplest form of the verb is called "the Root" of the verb ܥܸܩܪܵܐ ܕܡܸܠܬܵܐ . And all the verbs are constructed upon this root. In English, unfortunately, the verb is not categorized like it is in Assyrian, but this example might help:

From the verb 'like', we can derive these other verbs: liked, liking, have liked, had liked, will like, shall like, would like, would have liked and so forth. The simple form of the verb is 'like', but adding a few letters or words at the beginning or the at end of it, we can derive (build) other verbs.

In Assyrian, the root of the verb is the second part of the future tense of the singular third person (will go, without 'will' , would call, without 'would', etc.)

The best way of finding a root of a verb (in Assyrian) is to visualize the future tense, third single person of a verb, and then, take off the first part (the auxiliary word 'will'), [he] will take, [he] will come, ܒܸܬ ܫܵܩܸܠܸ، ܒܸܬ ܐܵܬܹܐ. Take off the first part of the verb, what is left, is the root of the verb, take, come. ܫܵܩܸܠܸ، ܐܬܹܐ

From the verb 'like', we can derive these other verbs: liked, liking, have liked, had liked, will like, shall like, would like, would have liked and so forth. The simple form of the verb is 'like', but adding a few letters or words at the beginning or the at end of it, we can derive (build) other verbs.

In Assyrian, the root of the verb is the second part of the future tense of the singular third person (will go, without 'will' , would call, without 'would', etc.)

The best way of finding a root of a verb (in Assyrian) is to visualize the future tense, third single person of a verb, and then, take off the first part (the auxiliary word 'will'), [he] will take, [he] will come, ܒܸܬ ܫܵܩܸܠܸ، ܒܸܬ ܐܵܬܹܐ. Take off the first part of the verb, what is left, is the root of the verb, take, come. ܫܵܩܸܠܸ، ܐܬܹܐ

Three weights of Verb as formulas

To simplify the vast variety of the verbs, they have been categorized through their roots into three categories:

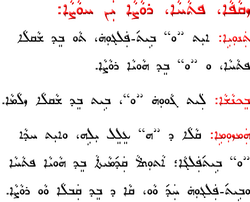

1. three letters: 1st. letter zqapa, 2nd letter zlama, 3rd letter silent (w/out vowel)

2. three letters: 1st letter ptakha, 2nd letter zlama, 3rd letter silent (w/out vowel)

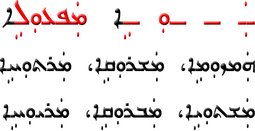

3. four letters: 1st letter ptakha, 2nd letter silent, 3rd letter zlama, 4th letter silent

Note: In the next few paragraphs, we will see how the zqapas and ptakhas are assigned.

1. three letters: 1st. letter zqapa, 2nd letter zlama, 3rd letter silent (w/out vowel)

2. three letters: 1st letter ptakha, 2nd letter zlama, 3rd letter silent (w/out vowel)

3. four letters: 1st letter ptakha, 2nd letter silent, 3rd letter zlama, 4th letter silent

Note: In the next few paragraphs, we will see how the zqapas and ptakhas are assigned.

What is the catch?

So, one might say, so what?! What is the big deal about the zow'ei, zqapa, ptakha or zlama and so forth! Why are we spending so much energy on these little dots!

They mean a lot, if not everything. They are the instruments in a song, salt in a food, buttons on a shirt or voice of a singer.

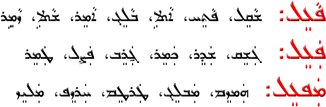

In our language, there are a lot of words that look alike, and without the vowels (zow'ei), they are hard to be distinguished between one another. The zow'ei or vowels, will make their differences clear. For example >>

They mean a lot, if not everything. They are the instruments in a song, salt in a food, buttons on a shirt or voice of a singer.

In our language, there are a lot of words that look alike, and without the vowels (zow'ei), they are hard to be distinguished between one another. The zow'ei or vowels, will make their differences clear. For example >>

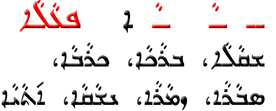

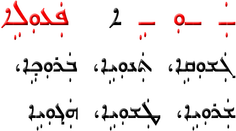

The patternThe three or four letters of the verb's root replace the letters in the patterns pa-il, paa-il and map-il, and carry the vowels of that particular pattern. These vowels will stay with the verbs in all varieties of that verb–tenses and nouns as long as the sound is the same, i.e, zqapa, ptakha, waow rwasa will stay the same, as shown in the example in front >>>>

|

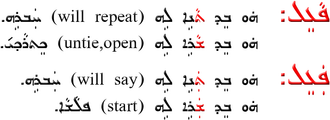

The Participle form of the verb

In English, the participle form of the verb is the present tense plus 'ing',

coming, going, writing, dancing, watching, talking, reading, skating, calculating, kidding, swimming, saying, telling, laughing, driving, running.

coming, going, writing, dancing, watching, talking, reading, skating, calculating, kidding, swimming, saying, telling, laughing, driving, running.

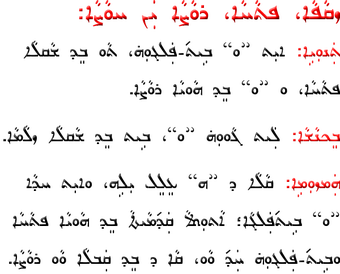

Spelling of the participle (in Assyrian)

So, we know by now that the root has either three letters or four. This is how the roots are spelled:

The first letter of the three letters roots will be either "zqapa" or "ptakha",

and the four letter root will always start with "ptakha".

The first letter of the three letters roots will be either "zqapa" or "ptakha",

and the four letter root will always start with "ptakha".

So, basically, to figure out the vowel of the first letter of a verb, find out the participle of it,

if it has a vowel "waow" in the middle, the first letter will be "ptakha", and the "waow" will be "waow rwasa".

if it dosen't have the "vowel waow", the first letter will be "zqapa"… It is that simple !

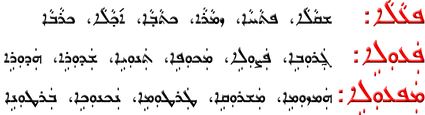

The significance of learning these formulas is that the rest of the verbs, and basically most of the vocabulary in Assyrian depends on them.

if it has a vowel "waow" in the middle, the first letter will be "ptakha", and the "waow" will be "waow rwasa".

if it dosen't have the "vowel waow", the first letter will be "zqapa"… It is that simple !

The significance of learning these formulas is that the rest of the verbs, and basically most of the vocabulary in Assyrian depends on them.

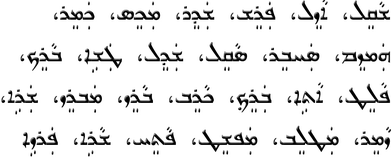

More samples of the "Weight" rule of the verb

Note: I have gathered these rules and samples from the book "Milta v Iqro" by the late Mr. Rabi Nimrud Simono (Misyo Benva). I typeset his books in mid 1970's in Tehran, Iran. The first time I was introduced to the rule of "Pa-il, Paa-il, Map-il was by late Rabi (Shamasha) Israel Alkhas, my other teacher in the Assyro-Chaldean Catholic Church.

To identify the correct vowel

So in order to see the first letter of the verb is zqapa ܙܩܵܦܵܐ or ptakha ܦܬܵܚܵܐ , and the waow in the middle (if any) is rwasa or rwakha, bring the verb into the participle tense ܙܢܵܐ ܠܵܐ ܡܬܲܚܡܵܐ , if there is a waow in the middle, the first letter will take ptakha ܦܬܵܚܵܐ ، and the waow will be rwasa ܪܘܵܨܵܐ .

|

A review on the 'weights' of the verb

So, for review take a second look at these verbs and recognize their 'weights'.